Book Review: Sexual Revolutions: Gender and Labor at the Dawn of Agriculture by Jane Peterson

- Gillian Scout Jaffe

- Jan 11, 2021

- 14 min read

By Gillian Scout Jaffe, Lucor Johnson, and Sally Robinson

Introduction

Jane Peterson’s book, Sexual Revolutions: Gender and Labor at the Dawn of Agriculture, seeks to shed light on the dynamics of labor organization at the dawn of agriculture. Her work explores the jobs people were doing, who was doing them, and how these factors shifted over time and in response to the changing labor demands ushered in by the “Neolithic Revolution,” as people became more sedentary and reliant on domesticated plants and animals for sustenance.

Reconstructing patterns of labor in human history is a difficult task. It is easy to unconsciously project current cultural norms onto the past when interpreting an archaeological record, taking for granted that the way labor is organized or divided by gender presently is the way it has always been. In Sexual Revolutions, Peterson attempts to subvert unconscious biases by rooting her analyses in the only direct evidence of labor patterns: skeletal data. In doing so, she brings a feminist archaeological perspective to archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence, and critique to previously conducted research. -GSJ

“Giving precedence to patterns in the data, with a clear-eyed view that we all construct the past, helps one avoid falling prey to essentialist assumptions that effectively remove sex and gender as analytic tools of interest for understanding social process,” (141).

Overview

Originally published in 2002, Peterson reviews archaeological evidence at a multitude of sites, dated from a period spanning 12000 years, in the southern Levant region. It is in this geographical area (which covers present day Israel and Jordan) and during this stretch of time that agriculture was first developed. Understanding how the division of daily tasks and workload evolved can provide insight into the development of gender roles and norms in association with sociocultural change.

The author is not the first to explore questions around gendered divisions of labor in this region, during the dawn of agriculture. In fact, much of the book is dedicated to reviewing the data and conclusions of archaeologists who came before. By assessing the original studied data in relation to conclusions drawn by the author, Peterson is able to identify which conclusions were grounded empirically, and which were cultural interpretations. For example, in reviewing a previous study from 1990, Peterson points out that the authors conclude that males were doing the fishing, even though their conclusions were based on scarce and limited data: two skeletons, one being of indeterminate sex.

What distinguishes Peterson’s work is her resolute adherence to a robust set of skeletal data. This data is comprised of measures of bone thickness; evidence of degenerative joint disease; evidence of trauma and disease; tooth wear and caries; and measures of entheseal change, also referred to as musculoskeletal stress markers (MSM). Her analysis operates under the theory that occupational stress leaves evidence on the bone, for example through highly porous and thickened muscle-bone attachment sites or linear grooves on teeth from processing fiber. Peterson then examines the skeletal evidence alongside other archaeological evidence from the sites (e.g. dwellings, foodways, lithic remains etc.). Again and again, Peterson refers back to what can be determined from concrete data and while she proffers different labor scenarios, she commendably only concludes what can confidently be supported by the data. This means that often her conclusions describe broad patterns over long periods of time, rather than site specific interpretations. While the level of detail put into measuring occupational stress could be daunting for someone with a limited background in anatomy or osteology, Peterson never assumes that the audience is made up of individuals who also have strong backgrounds in bioarchaeology.

Peterson uses a variety of methods of statistical analysis, as well as ethnographic evidence from other research, to put skeletal data into perspective. Statistical analysis allows clusters of similar MSM to be identified. Ethnographic evidence, while somewhat limited in applicability, is useful in determining possible types of activity associated with certain patterns or groupings of MSM. For example, she concludes that Natufian men may have been hunters based on the similarity in the set of MSM observed to MSM associated with the act of throwing.

The book is organized into six chapters. The first presents Peterson’s intentions for her investigation and introduces the reader to the geographical area and time period being studied. Chronology is divided into five time periods: Terminal Epipaleolithic (i.e. Natufian), Pre-Pottery Neolithic, Pottery Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Early Bronze I (EBI). The second chapter outlines a general chronology, and includes the archaeological evidence associated with each relevant period. This evidence forms the archaeological context for the bioarchaeological evidence being studied. Peterson also describes the current interpretation of each period’s social structure, family organization, and work, as well as the expected activities the people of each period might have engaged in based on the current evidence. The third chapter is devoted to describing the scientific basis for Peterson’s analytic tool: skeletal markers of occupational stress. In the fourth chapter, Peterson summarizes the results of other osteological studies done in the region related to occupational stress (73).

The meat of the book is the fifth chapter. It is here that Peterson presents her research by outlining the data set she used, her methods, and finally her results along with analysis and interpretation. Based on the temporal distribution of skeletons available for her analysis, she discusses the Natufian, Neolithic, and EBI periods. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic and Chalcolithic are not discussed due to the paucity of available data. Chapter five concludes with a diachronic analysis and interpretation of the results. The final chapter integrates the results of her MSM analysis into the larger discussion of gender dynamics, labor, and social organization in the southern Levant at the dawn of agriculture. Here, Peterson also presents her conclusions about changing labor patterns associated with the advent of farming and compares them to previous research on the subject. Finally, she reflects on her use of an engendered model of labor. -GSJ

“Humans have a role in shaping the culture process rather than being passive recipients of culture. Humans are not “pushed” and “pulled” around the landscape by changes in the physical environment and technology but are active participants directing culture change,” (192).

Methods

To understand the role of gendered activity practices and culture change across the five different time periods, Peterson used cluster analysis. Cluster analysis is an analytical technique that divides groups of certain things together based on similarities. For example, Peterson began by dividing the samples of human remains into categories of male and female. Then, she used rank ordering. Rank ordering is a way to categorize an assemblage from high to low or vice versa by exploring the differential use of specific muscles between groups of a study population (Kindle ed., Location 1171-1181). For instance, she took the tricep brachii (Figure 1) to see if there is a differentiation of tasks between men and women by examining their bones. She then breaks this into two categories (robusticity and stress lesions). She ranks robusticity from 1 - 6, where 1 is faint robusticity, and 6 is strong stress lesion (Kindle ed., Location 1717, 1745). I found that this was her most reliable line of evidence because she was able to measure what tasks were accomplished and by whom.

This figure compares the tricep brachii (found on the proximal end of the ulna) of someone (left) that had built up some faint robusticity and someone (right) that had built up moderate robusticity. While this is the most solid line of evidence and it is more visible in other figures with more examples, there are never any samples that are over 3.5. I am not sure if Peterson created this scoring method or if it was already established, but there were no samples that showed strong stress lesions, and that is a significant part of her analysis. The tricky thing about archaeology is that the farther one goes back in time, the less stuff there is to find. So, it may be that there were not any specimens collected that presented strong stress lesions, but that does not mean that there were not any at all. -SR

Results

Based on the example given above, the results showed that there are activities that certain genders do more frequently than others. For the tricep brachii, men had more robust triceps than women because they were hoeing and using sickle blades more frequently for farming purposes. Women, on the other hand, had more robust forearm muscles than men because they were continually grinding and processing the farmed goods. This muscle differentiation occurred in the Pottery Neolithic (8000 - 6200 BP), where there were gendered differences in activities (Kindle ed., Location 1942-2083). But, once the EBI occurs, the muscle differentiation between men and women of the farming/villager class is similar across the board. The differences in musculoskeletal are between social classes, where agricultural villagers had more robust muscles than the elites (Kindle ed., 2093-2181).

More broadly speaking, Peterson’s use of MSM allows her to make these accusations across thousands of years in the Levant region. In the Natufian period (12,500 - 10,500 BP), sexually dimorphic patterns occurred. As shown below, males had more prominent arm muscles (triceps, biceps, trapezius, and deltoid) than women due to potentially overhand throwing - relating to spear or atlatl hunting.

On the other hand, female musculature had more prominent forearm muscles due to more processing tasks that involve bilateral motions (Kindle ed., Location 2276). In the Neolithic period (10,500 - 6200 BP), male and female musculature became increasingly bilateral, showing similar MSM results. These results indicate that tasks were shared and muscles showing significant differences between the sexes decreased (Kindle ed., Location 2276-2286). Finally, the Chalcolithic and EBI (6200 - 5000 BP) suggest that female activity levels increase more than males. Peterson explains that male musculature diminished notably compared to the previous periods, but she infers that men and women had distinctive yet complementary tasks related to domestication and agriculture. These newfound tasks created shorter life expectancy and overall declining health, whereas the significant MSM differences were between the farming villagers and local elites (Kindle ed., Location 2286-2296). Overall, MSM contributed greatly to her driving question: is there gendered labor differences in the Levant region? And, seeing all of the results, I can say, and so can Peterson, that there is task variation between males and females in the Levant region. -SR

Contribution to Engendered Archaeology

Review of Literature

The authors are to be commended for presenting their findings in such detail. This presentation enables the reader to identify several interesting musculature patterns that, unfortunately, are not pursued. As one example, four individuals (one female, one male, two indeterminate sex) exhibit pronounced lateralization at the pronator quadratus insertion site on the ulna, with the left side showing more marked development. This suggests a unilateral activity(ies) pattern that is shared by males and females (134).

Part of what pulls the reader in is the social significance of the contribution to the literature that this work represents. Peterson introduces the reader to many of the past researchers contributing to the osteological research Levantine archaeology. This robust literature review hopefully helped us to address Boutin’s concern regarding historical narratives, “how does the use of skeletal data make these stories different from other types of archaeological narratives?” .

Peterson provides a great deal of deeply contextualized osteological data with clearly justified recommendations for how they reflect the lives of her prospective cast of characters despite the fact that she doesn’t attempt to weave these narratives herself. In order to understand what she brought to the table, a visitation in brief to the works which her work rests with is necessary. Early on the concentration was on identifying who was present in Levant over vast uninterrupted periods of habitation through studies of cranial morphology to explore relationships to extant populations, and change/migration over time. A new wave of research began late in the second half of the 20th century. Emerging from an interest in relationships between culture and biological evidence, the focus of research has shifted to what can be understood about the lives of the people there.

The author highlights several contributions from Levantine archaeologists focusing on osteological analysis and interpretation. The humeri cortical thickness from skeletons taken from El Wad and also ‘Ain Mallaha was compared to humeri dating from Middle Bronze I, the Roman/Byzantine, and the Early Arab period. Characteristics from male Natufian samples provided evidence of muscular development thought to be caused by spear throwing and atlatl use (Smith, Bloom and Berkowitz 1984). This dimorphism only existed prior to agricultural intensification in the area showing that later periods evidence of spear use disappeared.

In attempting to understand if food insecurity was worse for the gatherer/hunter Natufians, skeletal evidence of nutritional stress in human remains taken from five different Natufian sites: Kebara, Nahal Oren, Hayonim Cave, El Wad, and ‘Ain Mallaha, through this analysis it was able to be asserted that nutritional stresses were not an underlying factor in the lives of people there (Belfer-Cohen, Schepartz and Arensburg 1991).

Through extensive examination of femora, femora fragments, and other skeletal remains comprehensive comparisons of stature demonstrated that across the five agreed upon periods, female stature remained stable while male stature changed notably (Ratburn 1984). Identifying occupational stress in human skeletal remains requires identifying patterns of wear, grain processing from a kneeling position is thought to create identifiable patterns of stress on the toes, knee and lower dorsal spine while symmetrical development of the biceps and deltoids is also present (Molleson 1989, 1994, 2000). Peterson’s review of the literature, the placement and significance of her contributions are well presented, and the reader is left with a sense of things to come. Natufian sites at Atlit Yam and Nahal Oren provide a combination of evidences from occupational stress, flora and fauna, and fiber/cords has led to the assumption that terrestrial cultivation of plants and animals went hand in hand with aquatic resource exploitation (Hershkovits and Galili 1990). One occupational stress marker was the buildup of bone in the auditory exostoses, this is the result of deep sea diving. Here the authors attempted to reach past the data to argue fishing was a male activity.

The EBI and the Chalcolithic periods are extremely interesting to researchers for being important to building an understanding of life with farming being an integrated part of their subsistence strategy; for this reason it is extremely unfortunate that the periods have been studied very little. The picture which has emerged however is one that does not paint a rosy picture for agriculture’s early impact upon the body but there is not an agreement in the scant EBI. This was a time of extremely poor nutrition leading to decreased stature, loss of teeth and dental caries (Smith 1998b, 1995). It is important to note that despite widespread evidence of nutritional stress, there has been no evidence of it leading to interpersonal violence during these periods. Another of the few Early Bronze Period I creates likely evidence of interpersonal violence in the form of healed facial wounds thought to be caused by an ax impact. This period also brought the first signs of tuberculosis lesions that are thought to be connected to disease transfer between humans and animals as pastoralism placed ancestors in closer proximity (Ortner 1979, 1981, 1982).

Methodological Frame

“It is important to recognize that strictly defined sexual labor divisions are a corollary assumption often linked conceptually to the ‘nuclear family’. To many archaeologists nuclear families make sense because biological differences or culturally defined roles demarcate two distinct labor spheres for males and females. Thus, the dyad of one male and one female provides a complementary productive and reproductive unit. So reconstructions of the past that posit nuclear families as a primary socioeconomic unit implicitly suggest that sexual divisions of labor were already in place” (20).

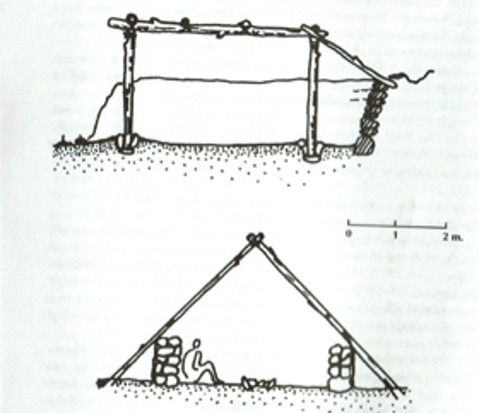

Throughout Sexual Revolutions: Gender and Labor at the Dawn of Agriculture, Jane Peterson’s work is clearly and effectively demonstrating four of the significant methodological developments of feminist and gender archaeology as listed by Elizabeth Brumfiel. Since much of the “task differentiation” requires some sort of inference, Peterson has committed to increasing “attention to the variability in gender relevant data” (Brumfiel 1996). One example is catching Byrd, Henry, and Olzewsky as they attempt to slip in an assumption of nuclear families in the Natufian period without any evidence except for the size of dwelling structures. Nuclear family groups attempt to bring in all sorts of presumptions about how gender is lived and enacted. The assertion is challenged by ethnographic data that based on the size of the dwelling, only one person would likely reside there meaning Natufian dwellings do not have to be read as implying heteronormativity, heteropatriarchy, or any other ideas about household dynamics or production (47).

Though ethnographic analogies can be helpful to observe how people live within extant communities in the region is extremely helpful, she provides three descriptions of labor which differ significantly (Peterson 26). Even now there is a great deal of variation both across geographic regions and across individual lifetimes; in fact in south Lebanon, whether you are a child or adult is more significant than whether you are considered male or female. On top of cautioning that remaining aware of variability is important, she mirrors Brumfiel by also highlighting the need for “increased caution in the use of ethnohistoric and ethnographic analogy in the study of gender”(Brumfeil 1996) such as the social and religious values within the practice of Islam which are relatively new and were not present in any of the periods of early agriculture in Levant but are the foundation in many gendered norms practiced now.

It is hard to address another of Brumfiel’s methodological developments in feminist and gender archaeology-- the “increased concern with the inclusion of women, men, and other genders in a single frame of analysis”. On the one hand, the entire book is devoted to making more space for the experiences of both men and women over their working lives in Levant during the five periods of subsistence-based habitation. The problem here is that while the whole book is devoted in this way, there is no discussion at all about what it means that the analysis is only situated on how to know what work biologically identified males and biologically identified females are doing based on osteological data. Gender and sex are predominantly treated as one in the same. This means that when sex can be determined, and it is concluded that work was likely conducted by mixed group, this is universally treated as lack of evidence of gendered division in labor rather than any sort of non-binary/fluid gender space within these communities.

The final of the significant methodologies present in feminist and gender archaeology is “new methods for ascertaining how gender was experienced” (Brumfiel 1996). Peterson outlines the choice to utilize musculoskeletal stress markers and cross sectional geometry to revisit samples gathered during previously conducted excavations in the area. New methods and new rigor led to some very interesting insights and critiques. For example, while the rigors of life are often clearly written on our skeletal remains, in order to calibrate this data it is important to know the age and these include maturity of the individual at the time of death. Identical wear patterns can depict either intensity or longevity of a particular stress. While it would be valuable to know the relative age of individuals upon their passing, the practice of removing the skull at or after burial and poor preservation of skeletal remains make it difficult. This means that while 158 skeletons were recovered from fourteen sites associated with the Natufian period, only 44.5 percent of adult skeletons could be given accurate age estimates and the remainder had to be labeled as “indeterminate adult”. -LJ

Conclusion

Sexual Revolutions integrates a wealth of data in addition to previous research to try and understand what can actually be known, and empirically supported, about the divisions of labor. Ever-present is the commitment to empirical analysis as she attempts to distinguish data-based conclusions from culture-based conclusions. While the specific activities associated with much MSM patterning is still to be delineated (and therefore specific activities of prehistoric people yet to be determined), Peterson confidently uncovers multiple patterns of workload and general labor that challenge previously held notions about the evolution of labor over time, and the effect of agriculture through this progression.

One of her goals was to include a critical feminist perspective while intentionally focusing “on sexual divisions of labor considered separately from questions of gender asymmetry and inequality,” (143). However, while the issue might fall outside her realm of inquiry, Peterson does not discuss in any way the relationship between biological sex and gender (her stance or others) and avoids acknowledgement of the commitment to gender as being implicitly tied to the biological sexual binary. Though some would argue that such matters are outside the scope of her MSM-based research, the conclusions she draws about these prehistoric societies are insufficient without some discussion of these themes.

While the systematic presentation of Peterson’s re-examination of the previous bioarchaeological research in the Levant region is persuasive and successfully places her contributions within the landscape of osteological inquiry of the time, the format and composition could, at times, be counterintuitive for linear engagement. The author’s review, research, and inquiry are thorough, but the organization and presentation could have been more effective. An easily identifiable revision would be to have devoted separate chapters to the interpretation of results as well as to the integration of results with previous research and current consensus. Alternatively, organizing the book by the periods examined might have enabled a more comprehensive understanding of the revolutionary agricultural age.

Despite these criticisms, the book is commendable as it resists the allure of grand conclusions that seduces many well-meaning researchers. The author clearly outlines the goals and limits of her inquiry and by the end, it seems she has met them. She stresses that the data presented from the southern Levant is simply one case, a drop in the bucket of bioarchaeological research on MSM, ripe for comparison to other cases and a contribution to an ever-growing global dataset. Peterson’s work successfully identifies erroneous conclusions of previous research and is, itself, a working-model of more rigorous and accurate methods of analysis and interpretation. -GSJ

Works Cited

Boutin, Alexis T.

2012 Written in Stone, Written in Bone: The Osteobiography of a Bronze Age Craftsman from Alalakh. In The Bioarchaeology of Individuals, edited by A. L.W. Stodder and A. M. Palkovich. University Press of Florida, pp. 193-214.

Brumfeil, Elizabeth.

2006 Methods in Feminist and Gender Archaeology: A Feeling for Differents and Likeness. In Handbook of Gender in Archaeology, edited by Sarah Nelson, pp. 31-58. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Peterson, J.

2002 Sexual Revolutions: Gender and Labor at the Dawn of Agriculture. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Comments